Odour capture

Odour capture – a remarkable Stasi tracking method

Everybody leaves unique traces – not just their fingerprints, but also their smell. Tracker dogs have been used to search for people for centuries. The professionalization of dog tracking first began in the 20th century, for instance through the collection of human odours on absorbent materials. The first move to establish a database of personal odours came in the 1970s. Established by the East German Volkspolizei, police technicians impregnated absorbent materials with odours found at a crime scene (the olfactory fingerprint). Storing this evidence in air-tight glass jars, the police trained tracker dogs to differentiate between smells and thereby tie suspects to the scene. Whilst this method was only applied to a limited number of cases, the Ministry for State Security (Stasi) routinized the approach, building up a massive archive of people’s smells. Started in 1979, the collection was kept across East Germany, collected and evaluated by the Main Department XX, responsible for monitoring the East German cultural and media scene and the repression of the political opposition. When rooting through the massive Stasi odour archives following the fall of the Berlin Wall, researchers were highly surprised at what they found.

One example of these odour samples is on view at the German Spy Museum. The label GK (the abbreviation for Geruchskonserve meaning “odour sample”) on the top left-hand corner of the jar indicates that this was a Stasi sample, as the Police used different markings. The label also specifies a registry number; the date and time at which the sample was collected; the name of the person from whom the odour had been collected; the crime scene from which the sample had been collected; the office responsible for collecting the sample; and the individual twelve-digit identification number assigned to every person in the DDR since 1970. All this information was duplicated in an index card system.

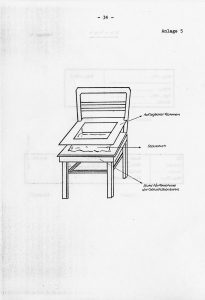

A number of different methods, both covert and overt, were used to gather the odour samples. They could be collected during a secret house search, taken from cars into which the Stasi had forced entry, or lifted from the scene of a crime. Suspects summoned for questioning were often seated on special chairs fitted with a sterile cloth which absorbed the person’s odour.

An odour sample did not constitute permissible evidence in court, and the archive was primarily used as an investigative tool with which to establish the identity of political opponents. For instance, the method was used to discover the identity of letter writers or the producers of protest flyers. The vast majority of these odour samples are stored in the central archive of the Federal Commission for the Records of the State Security Service of the former GDR (BStU).

Odour tracking was not the preserve of the Stasi: many Eastern bloc states and even the West German and Dutch Police employed smell to catch criminals in the 1980s. The last known use of an odour sample was made in 2007. The German Federal Prosecutor took odour samples from a number of anti-G8 activists. This procedure generated considerable debate and some criticism.